rasx() Screenshots: More Shots out at Slavery

This is the second batch of stills, following “rasx() Screenshots: Shots out at Slavery,” that throws me into the Good Ship Jesus—the slave ship of the mind. Somebody told me that it is better to be in The House Mourning than The WB Network House of Mirth. Oh, Lord: some mo’: “The Gummo Beloved”, “Vietcong Diva,” “Senegalese Undocumented Worker.”

The Gummo Beloved

Harmony Korine is guilty of not making white supremacist cinema. To say this again, in other, properly assimilated words, Harmony Korine wanted to make films inspired by his direct contact with social and natural environments. Harmony Korine calls this direct contact “realism.” In his IndieWire.com interview he says:

Harmony Korine is guilty of not making white supremacist cinema. To say this again, in other, properly assimilated words, Harmony Korine wanted to make films inspired by his direct contact with social and natural environments. Harmony Korine calls this direct contact “realism.” In his IndieWire.com interview he says:

I’m obsessed with realism. The only thing that matters to me in film and artwork is realism or the presentation of realism. But, at the same time, I realize that film can never be real and that movies are never real, even documentary falls short. Cinema verite is a fallacy. There is still a kind of manipulation involved.

1997 saw the release of Gummo. It’s an exploded view of “Middle America.” Korine declares:

I always felt that Middle America was interesting. Anytime that people do films about America, it’s always this kind of romanticized version, something that is just false, and I think it’s disgusting. I grew up in Nashville, so I wanted to make a movie with those people I grew up with. I wanted to make the first great American film about America, because I’m an American artist.

So dig baby: I would love to compare the box office or DVD receipts of Oprah Winfrey’s Beloved to Gummo. Perhaps the moneys will back me up when I say that Harmony Korine did more to communicate real, American whiteness to the world—the old-school whiteness capable of living with something so horrible as chattel slavery—than the excellent work of Jonathan Demme. The strong opinion here is that Harmony Korine successfully got his slavery message across without using a single Negro actor in costume chains.

See that black cat at the right. In the rasx() context, that cat represents an enslaved human being. Any random abuse the poor kids in Gummo want to pour out on the black cat has very little to do with sophisticated, intellectual, Bible-inspired, black-cat hatred. They just fuck with the cats because they, themselves, are all fucked up. In the fiction, the black cats are hunted for money by many characters in the film. And their motives and regard for the animals is very nonchalant, non-conscious, habitual. These American children live with a level of violence that makes great soldiers. This explains why the confederate army was so hard to beat at the beginning of the Civil War and how America kicks ass as the Fallujah policemen of the world. Elite, educated, white supremacists would never want this style and these themes to become a part of American youth culture. When white poverty is forced to see itself “realistically” it could get more difficult to raise an army. They don’t have time to give peace a chance because war makes too much money for the few and the proud: the elites.

See that black cat at the right. In the rasx() context, that cat represents an enslaved human being. Any random abuse the poor kids in Gummo want to pour out on the black cat has very little to do with sophisticated, intellectual, Bible-inspired, black-cat hatred. They just fuck with the cats because they, themselves, are all fucked up. In the fiction, the black cats are hunted for money by many characters in the film. And their motives and regard for the animals is very nonchalant, non-conscious, habitual. These American children live with a level of violence that makes great soldiers. This explains why the confederate army was so hard to beat at the beginning of the Civil War and how America kicks ass as the Fallujah policemen of the world. Elite, educated, white supremacists would never want this style and these themes to become a part of American youth culture. When white poverty is forced to see itself “realistically” it could get more difficult to raise an army. They don’t have time to give peace a chance because war makes too much money for the few and the proud: the elites.

There is a prostitution scene in Gummo with a mentally handicapped girl that eerily resembles a scene written by Toni Morrison in her novel Beloved where a father and son keep an adolescent African girl as a sex slave. Hey kids, you don’t need pornography and prostitution when you have cows and chattel slavery… White liberal Hollywood formalism needs to explain why this would be happening or such a scene would be “too problematic” to translate to film. Harmony Korine shows how such a scene should be done. Gummo explains to those rich white kids who don’t go to war—and some will grow up and have to explain themselves to the world on top of some bullshit Heritage Foundation—what it feels like to be poor and white. No delicate, scholarly edifices here—just raw whiteness. I am sure there are some liars out there proclaiming that the realism in Gummo is unrealistic.

Vietcong Diva

At left Gorodish played by Richard Bohringer speaks to Alba played by Thuy An Luu in Jean-Jacques Beineix, his 1981 film, Diva. Back in the 1980s, when I began to see this film, I never noticed the look in her eyes. Do you see the look in her eyes? Click on the picture to get a closer look. When I was a kid, all the way through to my 30s as a young, white liberal, I would be too busy seeing Gorodish as the brilliant hero.

At left Gorodish played by Richard Bohringer speaks to Alba played by Thuy An Luu in Jean-Jacques Beineix, his 1981 film, Diva. Back in the 1980s, when I began to see this film, I never noticed the look in her eyes. Do you see the look in her eyes? Click on the picture to get a closer look. When I was a kid, all the way through to my 30s as a young, white liberal, I would be too busy seeing Gorodish as the brilliant hero.

I was very impressed with Gorodish. I wanted to live in a large studio space just like Gorodish. I wanted identical cars just like Gorodish (with optional explosives). I wanted to have a spare lighthouse just in case I wanted to try new sexual positions with my pet Asian chick just like Gorodish. I wanted to be meticulous, artistic and technical just like Gorodish. And, of course, I wanted to take baths in a freestanding bathtub and talk shit to my spank just like Gorodish.

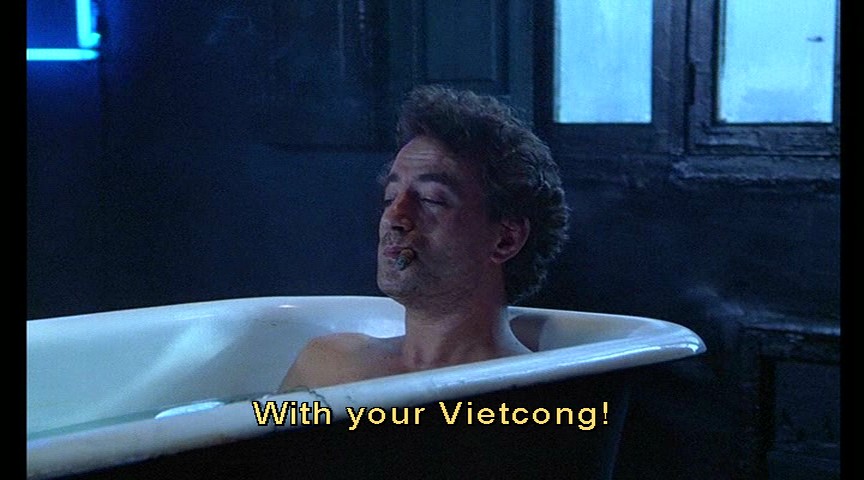

See him at right, taking a bath and speaking again to Alba. When I was child I understood completely that he was threatening her. But it took me decades to explicitly consider the possibility in writing that Gorodish keeps “his woman” not with good looks and technical excellence but with threats of deportation due to her ‘unspecified’ immigrant status. I consider the possibility that Alba is a sex slave.

See him at right, taking a bath and speaking again to Alba. When I was child I understood completely that he was threatening her. But it took me decades to explicitly consider the possibility in writing that Gorodish keeps “his woman” not with good looks and technical excellence but with threats of deportation due to her ‘unspecified’ immigrant status. I consider the possibility that Alba is a sex slave.

I remember the accounts of the French occupation of Indochina and their bitter defeat in the battle of Dien Bien Phu. Perhaps Gorodish is so adept with explosives and mind games because he was an agent of the colonial French government. Perhaps he has access to a lighthouse for professional and sentimental reasons—the light house was used to torture “the enemy”—and the old boys share it as a reward for their official service. Do you see the look in her eyes?

Now let’s not forget about a less-than-ideal Alba. She enjoys the sensations of the West and would dread living a hard, communist life in post-war Vietnam. Her message would be that it is better to be a slave in the West than to be free in abject poverty in the Far East. I need to find a character like Alba in a Vietnamese film so I can fully appreciate this message. The work of, say, Anh Hung Tran would have “mixed messages.”

You may notice that all this sexual attraction has not included the titled subject of this film Cynthia Hawkins, the Diva herself, played by Wilhelmenia Fernandez. The Cynthia Hawkins character eternally represents the inaccessible colored woman. There is only one scene in Diva where a non-white man got within three feet of Cynthia Hawkins: it was the character played by Raymond Aquilon, a charming street vendor. This message lasts to this day—even now at my age. Even after hearing financially and white-socially successful Negro women complain about Black men being “scared” of them and “insecure” around their “power,” I still say that this message lasts to this day. Without wasting my time trying to argue with Negro women who cannot see that they are not African women (even native-born African women running African governments), let me just say that the Diva story would have serious plot issues when you have Cynthia Hawkins up and down with a Black man. The Diva, “in love” with a Black man? That certainly would be another “terrible mystery”—right?

Gorodish is not a one-dimensional hero. He is definitely the type of character professional actors would love to play. But he should not be used as a role model for the adult incarnation of any human being. My childish instinct to follow patterns and imitate dominant human traits had me quite full of Gorodish dreams—and more silver screen characters like him. Now I consider myself mature enough to analyze Gorodish instead of being dominated by him. One piece of the analysis is the sexuality of Gorodish. I realize that his “sexual orientation” is different from mine. He has the sexual orientation of a mercenary—or really—an army man. What I find with me up to this day is the sexual orientation of a family man. I know all the Negro ladies out there—those cynical observers—are snickering sarcastically, “Yeah, right! You would trade places with him in a second.” Experience tells me to get beyond my sexism and consider the possibility that what my Negro sister is really saying is that she would trade places with Gorodish in a second. Set it off, girl!

Senegalese Undocumented Worker

A single still image at left taken from Ousmane Sembène’s La Noire de… (Black Girl) shows to me the pivotal moment when our heroine’s colonial fate is sealed. It is not for me to explain to you the entire plot of this movie. It is a very sincere film and is not difficult to grasp for those with the information and home training. What needs to be said here is that this still image shows the moment when the “black girl” tells her mother that she is about to go to work for white people in France. It is at this moment when her mother could have provided some statistical information about the probability that her living conditions—especially what is called her “spiritual” vitality—in France will be generative and healthy. When I imply the root word statistics I am not trying to be cute and coy. One of the roles of our elders is to provide useful, homespun census data. Our elders are supposed to be healthy and thoughtful enough to remember people other than themselves. Here in North America, this is often not the case. It is so reactionary and rebellious how young people consciously disregard almost all information from immediate family. The elders teach us. Even when they are not teaching us they are still teaching us. We need to listen—even when we are not being heard.

A single still image at left taken from Ousmane Sembène’s La Noire de… (Black Girl) shows to me the pivotal moment when our heroine’s colonial fate is sealed. It is not for me to explain to you the entire plot of this movie. It is a very sincere film and is not difficult to grasp for those with the information and home training. What needs to be said here is that this still image shows the moment when the “black girl” tells her mother that she is about to go to work for white people in France. It is at this moment when her mother could have provided some statistical information about the probability that her living conditions—especially what is called her “spiritual” vitality—in France will be generative and healthy. When I imply the root word statistics I am not trying to be cute and coy. One of the roles of our elders is to provide useful, homespun census data. Our elders are supposed to be healthy and thoughtful enough to remember people other than themselves. Here in North America, this is often not the case. It is so reactionary and rebellious how young people consciously disregard almost all information from immediate family. The elders teach us. Even when they are not teaching us they are still teaching us. We need to listen—even when we are not being heard.

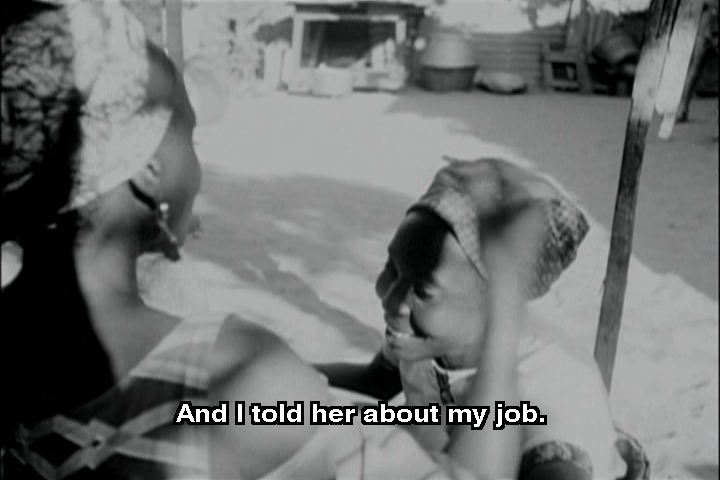

The next still at right shows me the reasons why young people—especially African youth all over the world—ignore the family elephant in the room. This image shows two African young people, the “black girl” and her beaux, looking at “continental” magazine before her departure to France. These two are being entertained and contained by the marketing wizardry of the west. They are completely absorbed and preoccupied by images that have nothing to do with them. The power of analytical existentialism allows them to surgically remove themselves from their present situation and transport themselves to a location that does not exist. They are fantasizing about bullshit—but, just like many youth of today, they would insist that they are “keeping it real.” What is disturbing is that this fantasizing is being dramatized in 1966—over 40 years ago! This bullshit is still going on now on a massive scale! Billions are being spent daily!

The next still at right shows me the reasons why young people—especially African youth all over the world—ignore the family elephant in the room. This image shows two African young people, the “black girl” and her beaux, looking at “continental” magazine before her departure to France. These two are being entertained and contained by the marketing wizardry of the west. They are completely absorbed and preoccupied by images that have nothing to do with them. The power of analytical existentialism allows them to surgically remove themselves from their present situation and transport themselves to a location that does not exist. They are fantasizing about bullshit—but, just like many youth of today, they would insist that they are “keeping it real.” What is disturbing is that this fantasizing is being dramatized in 1966—over 40 years ago! This bullshit is still going on now on a massive scale! Billions are being spent daily!

What is even deeper is that this has been going on for so long that there are very few elders with the home training to tell the African youth that this way of thinking is completely alien to pre-colonial African people, free from the influence of Indo-European imperial thought. (Let’s not forget about the “Arabic influence” that is murdering African people in Darfur today.) For most of us, these oral traditions are long gone. When I read “The Male” written by a man in South Africa on April 21, 2006, I see this loss in the flesh. My accusation against this South African citizen is that he fails to understand that the generation of his parents and his parent’s parents were deliberately mis-educated. The opinion here is that his report in “The Male” is an account of the cultural toxic waste left over from such missionary mis-education.

There is an implied disrespect here for the humanity of their parents and grandparents. Here is the racist irony: In our “fight” against “racism” we often depend on the mental traps of racism: just because a person has a certain skin complexion and because they happen to live on the continent called ‘Africa’ we assume that they are an African—and whatever sexist or violent behavior this chocolate-colored person produces must be African. This is the racist, missionary-trained assumption the children of Africa make about their forbearers. It is this pitiful line of thinking that permits so many of us to overlook the possibility that pre-colonial African cultures were deliberately designed and carefully developed over generations for functional (and often technical) reasons. African culture was not originally meant for us to be “proud” of so we can scare white people—it was designed to be used, implemented, incarnated on a daily basis that we may be fruitful and multiply. Much respect to The Lord, that brought us out of imperial Egypt, that what these words here are saying are not new. The recommended reading here is Facing Mount Kenya by Jomo Kenyatta.

There is an implied disrespect here for the humanity of their parents and grandparents. Here is the racist irony: In our “fight” against “racism” we often depend on the mental traps of racism: just because a person has a certain skin complexion and because they happen to live on the continent called ‘Africa’ we assume that they are an African—and whatever sexist or violent behavior this chocolate-colored person produces must be African. This is the racist, missionary-trained assumption the children of Africa make about their forbearers. It is this pitiful line of thinking that permits so many of us to overlook the possibility that pre-colonial African cultures were deliberately designed and carefully developed over generations for functional (and often technical) reasons. African culture was not originally meant for us to be “proud” of so we can scare white people—it was designed to be used, implemented, incarnated on a daily basis that we may be fruitful and multiply. Much respect to The Lord, that brought us out of imperial Egypt, that what these words here are saying are not new. The recommended reading here is Facing Mount Kenya by Jomo Kenyatta.

What continues to go unappreciated is the awesome power of white supremacy—most of this power is converted and refined from the human resources of “non-whites.” Too many Black people—and almost all white liberals—have very little respect for it. White power fossil-fuels one of the most profound mental/cultural revolutions in the history of the world. It is so powerful that it can reduce the healthiest “black girl”—selected by the universe to be fruitful and multiply with her dominant genes—to destroy herself. We don’t have to give away the plot in Sembène’s film. Let’s see the real “black girl” for a few sentences. Let’s start with her whole-hearted, indignant acceptance of the real toxic chemicals that weaken the strands of the hair on her head. Let’s start with the poison she calls food that she defiantly and indignantly places in her mouth on her way to diabetic obesity. White power is a triumph of the will over the laws of nature—and nature travaileth. It feels strange to remind human beings that they are ‘a part of nature’—such is the depths of whiteness. Whiteness is ready and willing for all takers of all skin colors. The West id the best. “Get here: we’ll do the rest.” For more appreciation of the work of Ousmane Sembène, see “David Mandessi Diop: To the Bamboozlers” here at kintespace.com.

This article was originally serialized over several days in the rasx() context, the kintespace.com Blog.