Achebe and the Problematics of Writing in Indigenous Languages

By Dr. Ernest N. Emenyonu

Two things emerged from the annual Odenigbo Lecture given by Chinua Achebe on September 4, 1999 at Owerri, Imo State, Nigeria. First, the lecture brought Achebe into a head-on collision with Igbo Linguistics scholars. Secondly, it forced scholars of Igbo Language and Literature to start debates again on the problematics of creating literature in an indigenous language in a multi-cultural, multi-lingual situation where a foreign language as official language, has gained national currency even at the grassroots and marginalised the status of mother tongues, as is the case in Nigeria today.

Two things emerged from the annual Odenigbo Lecture given by Chinua Achebe on September 4, 1999 at Owerri, Imo State, Nigeria. First, the lecture brought Achebe into a head-on collision with Igbo Linguistics scholars. Secondly, it forced scholars of Igbo Language and Literature to start debates again on the problematics of creating literature in an indigenous language in a multi-cultural, multi-lingual situation where a foreign language as official language, has gained national currency even at the grassroots and marginalised the status of mother tongues, as is the case in Nigeria today.

The controversy surrounding the Igbo Oral-Written interface is an age-long conflict dating to 1841 when a concerted effort was made by European missionaries to create a standard written Igbo from a wide variety of spoken Igbo dialects. What gives the present controversy a posture is that it is a clear cut battle between scholars of Igbo linguistics led by ‘Nolue Emenanjo, currently Rector of the Institute of Nigerian Languages, Aba, Abia State and creative artists led by Africa’s leading novelist, Chinua Achebe. Furthermore, the present controversy is more clearly defined in linguistic terms, what Donatus Nwoga appropriately labelled “the legislative dogmatism of grammarians versus the creative experimentations of creative artists.”

Sadly, however, the effect is the same now as in 1841. Writing in Igbo language has for more than a century been stagnated as each phase of the controversy creates fresh impediments not only for development of Igbo Literature but Igbo Language Studies in general.

To Achebe, Union Igbo was a mechanical standardization, and its use in the translation of the Bible into Igbo in 1913 was a legacy detrimental to the growth and development of Igbo language and culture. He charged Dennis furthermore of “tinkering” with the roots of Igbo language out of sheer ignorance of the natural process of language development in human societies.

The purpose of this paper is to come up with workable solutions that will move Igbo Studies forward in the 21st century. In four stages, the paper will discuss:

(a) the origins and substance of the controversy in which the Igbo Oral-Written interface is engulfed,

(b) Chinua Achebe’s 1999 Odenigbo lecture and the dimensions of the controversy it has engendered,

(c) analysis of the key issues and,

(d) proposals towards a lasting resolution of the critical issues.

The Origins And Substance Of The Controversy

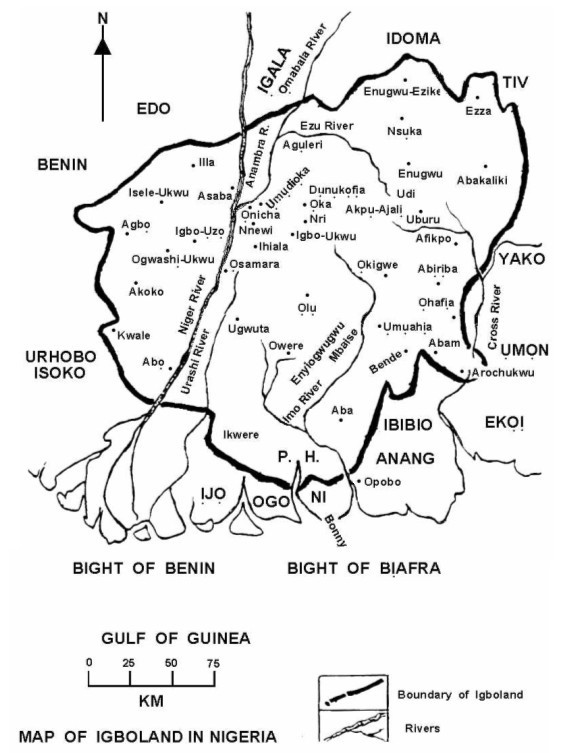

The Igbo language has a multiplicity of dialects some of which are mutually unintelligible. The first dilemma of the European Christian Missionaries who introduced writing in Igbo land in mid-19th century was to decide on an orthography acceptable to all the competing dialects. There was the urgent need to have in native tongue essential instruments of proselytization namely the Bible, hymn books, prayer books etc. The ramifications of this dilemma have been widening over the centuries in complexity.

Since 1841 three proposed solutions have failed woefully. The first was an experiment to forge a synthesis of some selected representative dialects. This Igbo Esperanto ‘christened’ Isuama Igbo lasted from 1841 to 1872 and was riddled with uncompromising controversies all through its existence. A second experiment, Union Igbo, 1905-1939, succeeded through the determined energies of the missionaries in having the English Bible, hymn books and prayer books translated into it for effective evangelism. But it too, fell to the unrelenting onslaughts of sectional conflicts.

The third experiment was the Central Igbo, a kind of standard arrived at by a combination of a core of dialects. It lasted from 1939 to 1972 and although it appeared to have reduced significantly the most thorny issues in the controversy, its opposition and resistance among some Igbo groups remained persistent and unrelenting.

After the Nigerian independence in 1960, and following the exit of European Christian missionaries, the endemic controversy was inherited by the Society for the Promotion of Igbo Language and Culture (SPILC) founded by F.C. Ogbalu, a concerned pan-Igbo nationalist educator who also established a press devoted to the production and publication of educational materials in Igbo language.

Through his unflinching efforts a fourth experiment and seemingly the ultimate solution, Standard Igbo was evolved in 1973 and had since then largely sustained creativity and other forms of writing in the language until 1978 when Chinua Achebe hurled the first “salvo’ challenging its linguistic legitimacy and socio-cultural authenticity. At the launch of a book, (The Rise of the Igbo Novel) published by the Oxford University Press which had in part explored the influence of European Christian missionaries on the development of Igbo Orthography and Written Igbo literature, Chinua Achebe strongly criticized the way the early missionaries designed an Igbo orthography, the Union Igbo, and imposed it on the Igbo people.

Achebe blamed the near stagnation of creativity in the Igbo language ever since on that dictatorial missionary manipulation. Since then, whenever and wherever Achebe had a chance, he continued unsparingly his attacks on the Union Igbo. Matters came to a head when His Grace, Dr. A.J.V. Obinna, Archbishop of the Catholic Archdiocese of Owerri invited Chinua Achebe from the United States to deliver the fourth in the series of a pan-Igbo annual lecture, Odenigbo in 1999. Odenigbo, a creation of Archbishop Obinna, began in 1996 as a deliberate interventionist initiative of the intellectually vibrant and philosophically astute scholar/prelate to foster and maintain an intra-ethnic discourse on matters of significance in Igbo socio-cultural development.

By having the lectures delivered in Igbo before a pan-Igbo audience and simultaneously published in Igbo language, Obinna sought to emphasize the homogeneity of Igbo people despite dialectal differences in speech. Furthermore, the exclusive use of Igbo language in the highly celebrated lectures ensured grassroots participation in the discourse unlike any other lecture series in existence with similar goals and objectives.

The choice of Achebe as the 1999 lecturer seemed also as an ingenious move to arrest an incipient suspicion in some quarters that Odenigbo was a religious more than a socio-cultural event, which drew its resources and inspiration from Igbo scholars who were first and foremost Roman Catholics. Chinua Achebe is a professing Anglican. Thus this choice was significant in that it bestowed credibility on Odenigbo as a pan-Igbo non-denominational cultural event open to all who have the survival, growth and stability of Igbo language and culture at heart. And nothing could have been more appropriate than Achebe’s chosen topic Echidiime: TaabuGboo (literally, “Tomorrow is Pregnant, Today is too Early to Predict…”)

Chinua Achebe’s Lecture

In his lecture, Achebe traced the history of missionary influence on the evolution of orthography for the Igbo language, and the process of the creation of Union Igbo as the standard for written Igbo at the turn of the 20th century. He adversely condemned the way and manner the standard was devised and blamed the chequered nature of the development of Igbo Language Studies since then on Archdeacon T.J. Dennis, the missionary whom he identified as the brain behind the creation of Union Igbo and its imposition on the Igbo.

To Achebe, Union Igbo was a mechanical standardization, and its use in the translation of the Bible into Igbo in 1913 was a legacy detrimental to the growth and development of Igbo language and culture. He charged Dennis furthermore of “tinkering” with the roots of Igbo language out of sheer ignorance of the natural process of language development in human societies. In that process, Achebe alleged that Dennis had in his missionary over zealousness and colonial mentality done irreparable harm to Igbo language in particular and Igbo life and culture in general.

And then by extension, Achebe condemned and derided present Igbo Linguistics scholars who, it seemed to him, had followed Archdeacon Dennis’s subversive linguistic approach by making and imposing dogmatic rules on Standard Igbo evolved in 1973. He called such scholars “disciples of Dennis” and alleged that they too had unwittingly done more harm than good to the development of contemporary Igbo Language Studies.

He charged that their various dogmatic impositions on the Igbo language, when compared to the strides made in Yoruba and Hausa studies, was responsible for the slow pace of Igbo Language Studies. Achebe pointed to the stability in the Yoruba language development and studies as a credit to another missionary, Adjai Crowther, who had a totally different approach in the process of selecting a standard for written Yoruba language. Achebe was convinced that Crowther owed his success to his sensitivity to Yoruba language of which he was a native speaker. In the Yoruba model one dialect, the Oyo dialect, was selected early and nurtured into the standard for writing in Yoruba language.

Perhaps what was most revolutionary in Achebe’s Odenigbo Lecture was not what he said but rather what he did. Two decades after his initial condemnation of Union as well as Standard Igbo, Achebe had not shifted from his position that Igbo writers should be free to write in their various community dialects unencumbered by any standardization theories or practices. Then as now, he resented attempts to force writers into any strait jackets maintaining unequivocally that literature has the mission “to give full and unfettered play to the creative genius of Igbo speech in all its splendid variety, not to damn it up into the sluggish pond of sterile pedantry.” In keeping with this principle, therefore, Achebe wrote and delivered his Odenigbo lecture in a brand of dialect peculiar only to Onitsha speakers of the language and almost unintelligible to more than half the audience.

He was making an unmistakable millennium statement which would be hard to miss by those Igbo Linguistics scholars whom he had once referred to as “egoistic schoolmen who have been concerned not to study the language but to steer it into the narrow tracks of their particular pet illusion.”

The organizers of the lecture were forced to do the unprecedented: printing in the same booklets two versions of the 23-page lecture, one, Achebe’s original version, and the other in the conventional Standard Igbo. The climax of Achebe’s position on the Igbo Oral-Written interface was his call for the total abolition and the scrapping of Standard Igbo in which the Igbo language has been written and accepted by scholars since its evolution in 1973.

The danger about resorting to name calling in the course of an important discourse is that it distracts from the main focus of the essential argument. The issue of deciding on a standard for writing Igbo so that Igbo Language Studies can move on is too paramount to be sacrificed at the altar of rhetoric and polemics.

Nothing could be more divisive at a forum assembled to celebrate Igbo Studies who had looked forward to the early decades of the 21st century as the era for Igbo Renaissance after over a century of fratricidal acrimonious controversies first over the choice of a pan-Igbo orthography and then over the standardization of written Igbo.

Reactions to Achebe’s views in the lecture were predictably fast especially from Linguistics scholars devoted to the theory and cause of Standard Igbo.

Reactions to Achebe’s Views:

Innocent Nwadike

Achebe’s lecture drew many reactions both positive and negative but more the latter. The most detailed and indeed the most negatively extreme came from Innocent Nwadike an Igbo language lecturer at the University of Nigeria, Nsukka, who is apparently totally dedicated to the cause of Standard Igbo as evident in his tone and language. What strikes the reader about Nwadike’s article, “Achebe Missed It”, published in a Nigerian weekly magazine (The News, March 27, 2000), was not the substance of Nwadike’s disagreement with the views of Achebe, or his right to do so, but rather his compunction to deride and insult, as can be seem in the following excerpts:

Achebe had nothing to offer his audience except throwing of sand… Achebe’s lecture turned out to be real throwing of sand which ended in pronunciation of the heresy of the last century of the second millennium… Achebe’s tragedy and failure started when he descended from his Olympian… to copy without verification…

Achebe was led astray and he marshaled out many historical fallacies… Though Achebe has persistently stressed his unalloyed love for Igbo language, he has done nothing towards its promotion and growth, except continued destructive criticism since the 1970s… In the course of his lecture, Achebe leveled many false accusations against Dennis and very heart-breaking are the lies against the dead…

Anyone who reads Achebe’s lecture will notice an air of superiority and worldly triumphalism exhibited by the author almost arrogating to himself transcendental power which belongs to God alone…

Let him (Achebe) as from today, learn to respect his people and all constituted authority…

Let not Achebe constitute himself a cog in the wheel of progress like one Chief Nwakpuda of the Old Umuahia who tried to stop a locomotive engine from passing through his village…

Achebe should stop embarrassing himself, for a beautiful face does not deserve a slap as the Igbo say…

The danger about resorting to name calling in the course of an important discourse is that it distracts from the main focus of the essential argument. The issue of deciding on a standard for writing Igbo so that Igbo Language Studies can move on is too paramount to be sacrificed at the altar of rhetoric and polemics. Although in the Igbo republican culture, freedom of expression is encouraged and cultivated, and a child who washes his hands could eat with kings, this is not an invitation to anarchy and the denigration of hierarchy.

The critical method in literary criticism is as important and significant as the substance of the criticism. How one says something in an Igbo gathering is as crucial as what one has to say and perhaps more so. Nwadike’s ungracious choice of words, his personal attacks on Achebe and his apparent glowing in subjecting Chinua Achebe to public ridicule is, to say the least, most unfortunate and quite antithetical to the Igbo cultural norm which restrains a child from jesting at, ridiculing, or speaking in utter derision of an elder, no matter the facts of the case.

The Igbo have a saying that the public ridicule or disgrace of a titled elder is more painful than his execution. Chinua Achebe is not a reckless man, and not the least a careless writer. If anything he is a man who thinks carefully about issues, a conscious artist who is quite cautious in his choice of words for public utterance. He would as the Igbo say, look to his left and to his right before crossing the road. And, Igbo wisdom admonishes the onlooker to carefully search the direction to which a weeping child is pointing, for the child’s mother or father may well be there.

We applauded when on behalf of the African continent, Chinua Achebe single-handedly took on the obnoxious institution of European colonialism and flawed it. We fully concurred when Achebe, on behalf of African culture and dignity, reduced to size the egocentric, egoistic, and presumptuous early Christian missionary and colonial administrator. We applauded Achebe’s heroic and altruistic vocabulary in his novel Things Fall Apart when he lashed at the irreverence and high handedness of the early Europeans who came to Africa:

Does the white man understand our custom about land? How can he when he does not even speak our tongue? But he says that our customs are bad; and our own brothers have turned against us? The white man is very clever. He came quietly and peaceably with his religion. We were amused at his foolishness and allowed him to stay. Now he has won our brothers and our clan can no longer act like one. He has put a knife on the things that held us together and we have fallen apart. (124–5)

In his Lecture, Achebe seems to be charging not at the misshapen European bull but the lamb at the sublime shrine of his people’s spiritual existence. He once declared that a language is more than mere sounds and words; indeed a language is a ‘people’s world view.’ A language is a sacred symbol of a people’s humanity. A committed African writer carries the burden of the conscience of his community. Chinua Achebe has positioned himself at the forefront of the committed African writers who use art to better the lives of their fellow men and women; who use art to restore the lost dignity of the African past, writers who use art as a celebration of life in the present. So rather than dismiss Achebe’s views arbitrarily or hastily, we should examine them thoroughly and inform ourselves whether the spokesman of African cultural realism and renaissance had in fact missed the point about what is best for his own people’s language and culture, whether in the full glare of bright lights, Chinua Achebe had misread the colours of the garments in his innermost closet. Only then can we look him fully in the eye and say the novelist lied!

Nwadike’s ungracious choice of words, his personal attacks on Achebe and his apparent glowing in subjecting Chinua Achebe to public ridicule is, to say the least, most unfortunate and quite antithetical to the Igbo cultural norm which restrains a child from jesting at, ridiculing, or speaking in utter derision of an elder, no matter the facts of the case.

Analysis of the Key Issues

Two supreme facts have to be established unequivocally at the onset. First, there is a Standard Igbo in existence; it is a reality; it cannot be set aside. It is not perfect but it is the best framework we have in existence for further development and improvement. It is a major legacy left for Igbo Language Studies by the Society for the Promotion of Igbo Language and Culture, (SPILC) and its inimitable founding president, the late F.C. Ogbalu.

In an August 1974 seminar of the SPILC, a Standardization Committee was set up. It was all embracing in composition. “Lecturers of Igbo Studies at institutions of higher learning, authors, publishers, broadcasters, teachers of Igbo language in secondary schools and teacher training institutions, representatives of the Ministries of Education and Information, State Schools Management Boards and the Mass Media.” Since 1974, substantial improvements have continued to be made on the final product of the Standardization Committee. There is now in existence a very useful supplement, Igbo Metalanguage, produced under the auspices of the Nigerian Educational Research and Development Council (NERDC) which also sponsored the production of the Yoruba Metalanguage and Hausa Metalanguage. Igbo Metalagnauge serves as a common reference for writers, teachers and examiners. It is a useful glossary which is an invaluable guide for anyone who wishes to learn the application of Standard Igbo in creative or other writings.

The second incontestable fact is that Igbo Language Studies and Development currently, as has been the case for almost half a century, lag behind the other two Nigerian major languages—Hausa and Yoruba. As Donatus Nwoga pointed out in his exceptionally brilliant study, From Dialectal Dichotomy to Igbo Standard Development, the National Language Policy in Nigeria has been a major catalyst in the development of educational materials in the three languages designated as major. Nigeria which speaks 394 indigenous languages has given up choosing an official language from among them, but instead settled for English, a colonial inheritance as its language of business, education and government. The National Language Policy has identified three languages Hausa, Igbo and Yoruba as major and requires them to be studied in schools as a means of advancing the theory that “first language education is the best tradition in the early years of the educational process”.

This policy has greatly enhanced the production and publication of educational materials, texts and literature in the three major languages. The population of the Igbo speaking people is at least the third highest in Nigeria’s estimated 120 million population. It is a fact, however, that Hausa and Yoruba scholars and writers have made greater and far more impressive strides in the development of teaching and reading materials in Hausa and Yoruba languages than their Igbo counterparts have done for Igbo language. It is most likely also that outside Nigeria, Igbo is the least studied of the three languages. The reason is not far to find. The endless squabbles over orthography, standardization and the like, can hardly inspire interest and excitement in prospective learners in and outside Nigeria. Igbo people have not put their house in order and people do not waste time on something or a situation in chaos. It is, therefore, in the best interest of the Igbo people and Igbo Studies that the present crisis be resolved quickly and in the best possible manner so that Igbo Studies can take its rightful place in the academy.

Nigeria which speaks 394 indigenous languages has given up choosing an official language from among them, but instead settled for English, a colonial inheritance as its language of business, education and government.

Two other issues deserve close critical attention because of their centrality in any possible solutions for the issues under review. First, to what extent should we blame Archdeacon Dennis for the stagnation and tardiness in Igbo Language Studies because of his invention of Union Igbo as the medium of translating the Bible into Igbo language in 1913? Secondly, can we set aside the work of the Standardization Committee of 1974 as a compromise for moving forward Igbo Language Studies in the 21st century?

It will be quite absurd to blame Archdeacon Dennis for the instability in the Igbo Language Studies for an alleged error in linguistic judgment made almost a century ago. It will be like blaming the British for the misrule and instability in the Nigerian government since the attainment of independence in 1960. Nigerians have had half a century to right the wrongs, correct the anomalies, refocus the directions of the country and stamp out unprogressive legacies planted by the British at their exit. To continue to blame Archdeacon Dennis for our woes will be tantamount to saying that the issues of orthography and standardization have been stagnant and un-revisited since 1913. Yet we know that some Igbo Language scholars have invested considerable amounts of time and energy in the last three decades at least, into researches in Igbo Language and Culture.

Can we easily forget or afford to ignore the tremendous works of late F.C. Ogbalu and Donatus Nwoga; or the continuing endeavours of Ebo Ubahakwe, Nolue Emenanjo, M.J.C. Echeruo, Chukwuma Azuonye, B:I.N. Osuagwu, G.E. Igwe among others? These scholars have in their studies made tremendous strides to move Igbo Language Studies forward. We must, therefore, reject any approach that negates gained grounds. Any new studies must build in the noble achievements of previous endeavours.

So instead of taking 1913 as our point of reference, we must turn to achievements since 1982 and build on them. Nor can we close our eyes to Archbishop A.J.V. Obinna’s 1996 landmark action towards a renaissance of Igbo Language Studies. It is regrettable to discuss the Odenigbo Lecture series as simply a “closed-door” religious and Roman Catholic event. Or to see the prelate as seeking to upstage the paraplegic Ahiajoku Lecture initiated by the Imo State Government in 1979. Obinna is nationally and internationally recognized for his ardent interest and commitment to the preservation of Igbo Language and culture in particular, and the arts and humanities in general. It was not a surprise to keen observers that he initiated the Odenigbo Lecture series. He would have done no less if he were an Anglican, Baptist or Methodist Archbishop or for that matter if he held the sacred ofo of the traditional religion in his Emekuku village near Owerri.

Many Igbo scholars had greeted with overwhelming enthusiasm a similar vision by the late Gaius Anoka when his brain child, the Ahiajoku Lecture series, was initiated under the auspices of the Imo State Government and designated to be delivered yearly in November. By the early 1990s Igbo scholars had begun to witness with dismay the derailment of the noble objectives of the Ahiajoku Lectures owing largely to self defeating manipulations and in-fightings by government bureaucrats. Ahiajoku simply became one more government event and like many things in government and civil service, it became the community goat that always died of hunger.

Archbishop Obinna’s initiative came just in time to arrest total public disenchantment in what had started off as a dynamic and progressive renaissance in modern Igbo culture. Since the end of the Nigerian civil war in 1970, the Igbo people seem to have developed a bewildering self destructive tendency, with a sharp instinct for killing their best. Progressive ideas are treated with levity and cynicism. Novel initiatives for development are scoffed at and opposed to the bitter end and when they are crushed, we realize too late that the perpetrators had nothing much to offer and in most cases, nothing at all. In the fifth year of Odenigbo, the Imo State Government suddenly woke up from almost a decade of amnesia and slumber to remember Ahiajoku and immediately picked one more lecturer who spoke to a pan-Igbo audience, about sacred ancestral Igbo culture and customs, in the English language! If history is anything to go by, Ahiajoku will sooner or later make another jay-walk into coma. It is on record that Archbishop A. J. V.

By the early 1990s Igbo scholars had begun to witness with dismay the derailment of the noble objectives of the Ahiajoku Lectures owing largely to self defeating manipulations and in-fightings by government bureaucrats. Ahiajoku simply became one more government event and like many things in government and civil service, it became the community goat that always died of hunger.

Obinna and the retired Anglican Archbishop B. C. Nwankiti in 1998 stood unflinchingly firm against all odds, in their opposition to the desecration of Igbo artifacts, historic sculptures and other spectacular works of art by an Islamic-minded Military Governor-turned-born-again Christian, in the name of presumed reverence for the sanctity of a new found Christianity. It is one thing to denigrate Archdeacon Dennis who may deserve it; it is another to try to undermine the heroic efforts of Archbishop Obinna who does not deserve it at all.

If we may return to Archdeacon Dennis, one final word is in order. Saint or sinner, let us allow Archdeacon T. J. Dennis, his Union Igbo, and his tinkering with the Igbo language, to go down in history as among those sad and costly prices which Nigeria had to pay for being subject to an imperial overlord who rode roughshod over our God-given languages, sacred customs and traditional cultures. And let’s move on!

Let us now turn attention to the second issue namely, “Can we set aside the present Standard Igbo as a necessary compromise for Igbo social unity and cultural homogeneity, and attempt a fresh start?” What has been discussed so far is substantial enough to indicate that setting aside the present Standard Igbo will not only be retrogressive but indeed suicidal. What is happening to Igbo language today with its multiplicity of dialects, and strivings to find a standard, is not a peculiar phenomenon. Germany had its language problems. England had its own. Finland evolved Standard Finis as the solution to her dialectal problems at the end of the 19th century. Can we learn anything from each model and each approach? The best model of Igbo written language will be the one that is accessible to or has potentials of being accessible to Igbo people across the board.

Often it is simplistically assumed that the Yoruba next door, achieved their Standard Yoruba without rancour and schism, and that the selection of the Oyo dialect by the missionary, Adjai Crowther in 1842 had never been challenged to date. Nothing could be farther from the truth. The Yoruba had something which was lacking in the Igbo traditional society namely, the institution of royal paramouncy as a central authority which exercised political power of a controlling nature. The Igbo instead, had a decentralized political system which put a central controlling authority out of the question. Establishing a Standard in any language is a political action and is often accomplished where there is political control along with economic initiatives. It becomes easier to establish and enforce a language policy relative to the language of the group with dominant political power.

Often the dialect of the dominant political group became the Standard, and political and economic instruments were used to sustain and legitimize it. The decentralized and political nature of the Igbo as a group has not made the standardization process easy. The fragmented Igbo set up, which was a source of strength in the past, has become a liability in the present. What has worked for the Yoruba has not worked for the Igbo but it was not only because the Yoruba had traditional rulers who exercised central authority. The Yoruba had their full share of controversies over orthographies and dialects. The Oyo. Ijebu, Ondo, Ekiti, Ijesha, Igbomina, Kabba all staked their claims.

But there was political intervention when following the Nigerian Independence, Chief Obafemi Awolowo then Premier of the Western Region introduced Free Primary Education in this Region of Nigeria and decreed that the Yoruba language to be taught in the schools would be the Oyo dialect. That was a major factor in the stabilization of Standard Yoruba.

If we may return to Archdeacon Dennis, one final word is in order. Saint or sinner, let us allow Archdeacon T. J. Dennis, his Union Igbo, and his tinkering with the Igbo language, to go down in history as among those sad and costly prices which Nigeria had to pay for being subject to an imperial overlord who rode roughshod over our God-given languages, sacred customs and traditional cultures. And let’s move on!

But standardization does not mean the death of sectional dialects. The spoken language need not be identified as synonymous with the written standard. Political intervention was a great catalyst in the creation of the modern Standard Yoruba but Yoruba Linguistics scholars did not rest on their oars. They devised some linguistic mechanism for solving the problems created in the process of standardization. They fished out words from other dialects to satisfy new demands which could not be met by the Oyo dialect. They created the policy of mutual give and take among the various dialectal groups for the purpose of enriching the Standard. Yoruba Linguistics scholars disagree as will always be expected in academic circles, but they never lose sight of their collective responsibility to standardize the language in the interest of the unity and identity of all Yoruba people. This commitment to a collective goal has yielded immense dividends in Yoruba Language Studies.

The Yoruba alphabet was introduced in 1842 by the early Christian missionaries as was the Igbo alphabet about the same time. The first novel in the Yoruba language was published in 1928 not far from the first Igbo novel, Omenuko, published in 1933. The father of the Yoruba novel, D.O. Fagunwa, began writing in 1938, the same decade as Pita Nwana, the father of the Igbo novel. But today the Igbo cannot boast of half the literary ouput that exists in Yoruba language: a corpus that includes 185 novels, 80 plays and large numbers of collections of poetry and translations of other works into Yoruba. In addition, there are in existence volumes of Yoruba Metalanguage; A Glossay of Yoruba technical Terms in Language, Literature and Methodoloogy as well as several Yoruba grammar books and reference works. There are translations of the Nigerian Highway Code in Yoruba.

Although Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart is a classic novel that incomparably depicts Igbo culture and worldview, the only translation of it in a Nigerian language is the Yoruba edition published in 2000. The Yoruba Writers Association was established in 1982 and is still going strong and increasing its cultural and educational impacts on the growth and development of Yoruba Language and Literature. Igbo linguists, scholars and writers can learn something from the Yoruba at least their intellectual attitude of accommodation and their commitment to the collectivist goal of advancing the development of Yoruba Language Studies from one generation to the other despite differences in the Yoruba which they speak in their intra-ethnic forums.

Dr. Ernest Emenyonu is Professor and Chair of the Department of African Studies, University of Michigan-Flint. He has taught and published widely on African Literature in Africa and the United States. According to biafranigeriaworld.com, this article first appeared in Guardian, Saturday, December 15, 2001.