rasx() Screenshots: Freestyle—The Art of Rhyme

Freestyle—The Art of Rhyme

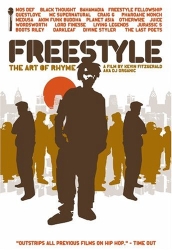

directed by Kevin Fitzgerald is another professionally made ‘home’ movie from my big African family, spreading from the enclaves of Los Angeles throughout the world. It is one of the few hip-hop “culture” films that pays serious respect to the West coast outside of the context of “gangsta rap.” It’s focus on the freestyle form of flow renews the symbolism the “wild” West represents to many an escaped slave who does not want to play cowboy. Since I was born and raised in Los Angeles and was involved personally with many of the subjects shown in the film, I am more than motivated to bring DVD extras to this feature.

Freestyle—The Art of Rhyme

directed by Kevin Fitzgerald is another professionally made ‘home’ movie from my big African family, spreading from the enclaves of Los Angeles throughout the world. It is one of the few hip-hop “culture” films that pays serious respect to the West coast outside of the context of “gangsta rap.” It’s focus on the freestyle form of flow renews the symbolism the “wild” West represents to many an escaped slave who does not want to play cowboy. Since I was born and raised in Los Angeles and was involved personally with many of the subjects shown in the film, I am more than motivated to bring DVD extras to this feature.

B. Hall and Ifa Sadé

Two women can be credited for starting the freestyle hip-hop school on the West Coast. One of the women, Ifa Sadé, is an ancestor. She is shown in the picture frame in the lower right hand corner of my Blog entry, “Two Stills from KRST Unity.” The other woman, B. Hall, is shown at left. Ifa Sadé was the principle partner of The Good Life Heath Food Restaurant with her husband Omar that housed the rappers one night per week throughout the 1990s. B. Hall was the organizer of the concept. B. Hall is literally the producer.

Two women can be credited for starting the freestyle hip-hop school on the West Coast. One of the women, Ifa Sadé, is an ancestor. She is shown in the picture frame in the lower right hand corner of my Blog entry, “Two Stills from KRST Unity.” The other woman, B. Hall, is shown at left. Ifa Sadé was the principle partner of The Good Life Heath Food Restaurant with her husband Omar that housed the rappers one night per week throughout the 1990s. B. Hall was the organizer of the concept. B. Hall is literally the producer.

Beyond what was edited into this award-winning documentary is the fact that B. Hall is the mother of R/Kain Blaze, The Undefined. It was he who did the day-to-day groundwork that made the “The Good Life” open-mic’ happen. It was he who produced the underground magazine freestyle at the same time Urb and The Source were coming of age. The goal was to respect the freedom in “freestyle” and build a youth-owned media center based on the content produced out of The Good Life and the human traffic packed in each night. What happened was that most of the twenty-something talent kept it real, obeyed the laws of instant gratification and commerce and embraced those high-interest loans we call record deals as quickly as you can run out of a box of promotional stickers among the light poles of inner-city boulevards. To rewrite a line in Volume 10’s “Pistol Grip Pump,” Hang with the dogs, man. Forget the guerilla.

The Undefined, by the way, is interviewed here at kintespace.com where you may find it curious that this man is a seasoned filmmaker but it took someone else to make Freestyle—The Art of Rhyme. Simultaneously, I am having difficulty recalling that any of the gold-record-producing rappers coming out of The Good Life banding together to do a benefit concert for B. Hall, who is not by any stretch of the imagination a “wealthy” woman.

Most African-descended children, those of “the darker tone”—to quote one New Yorker in the film—are conditioned to survive into adulthood as disconnected, egocentric individuals. So when we see one of the rappers in the film screaming at the top of his lungs in the crowded parking lot of The Good Life “Let me get down!,” I can assure you that he is not thinking about the wellbeing of B. Hall, Ifa Sadé or R/Kain Blaze. Disrespect comes naturally—even subconsciously—for captives of the oppressor, as the Wicked Master is the role model. It takes a genuine-human effort to overcome the Imperial Conditioning and bring Black Africa.

The Good Life Stage

When a young poet of the year 2005 can no longer stand my negative comments about 2005, Los Angeles poetry venues, like the show at Greenway Court Theatre, I must remember that such a young person does not share the vibe barely captured in the grainy image at left from the early 1990s of the stage at The Good Life from Freestyle—The Art of Rhyme. We have different memories, being different people from different times. What we see and feel looking at this image are most likely of two very different minds. As one speaker in the film says, there were nights in The Good Life that were “sublime” and this image reminds me of those nappy-few moments.

When a young poet of the year 2005 can no longer stand my negative comments about 2005, Los Angeles poetry venues, like the show at Greenway Court Theatre, I must remember that such a young person does not share the vibe barely captured in the grainy image at left from the early 1990s of the stage at The Good Life from Freestyle—The Art of Rhyme. We have different memories, being different people from different times. What we see and feel looking at this image are most likely of two very different minds. As one speaker in the film says, there were nights in The Good Life that were “sublime” and this image reminds me of those nappy-few moments.

Most of the Good Life people back then were young enough to still remember how to be authentically joyful and improvisational—simply playful. No upper-class, “success oriented” pretensions and tensions… But without an African life science to study law to become lawful and fruitful, eventually many homies would end up “dropping science” and playing themselves with dope tracks of narcosis… but for a brief moment, freestyle bliss…

There was one speaker in the film who reminded me of the complaint many sucker MCs had about the “censorship” imposed upon them at The Good Life. To use his word, when you saw the mic’ at The Good Life you could not “curse.” Since these freestyle youngsters were supposed to be using words when they rhymed let’s really get down into them. You have a voice saying that they felt censored because they were unable to curse. Such a dumb-ass motherfucker should feel censored because they are unable to bless. Who’ J’ah bless, no one can curse.

The Good Life Stage Redux

The Good Life was packed—to bite line from De La Soul—The Good Life was darkly packed. American traditional values used to make it formally and explicitly illegal for Africans to come together in public. So the image at left from Freestyle—The Art of Rhyme has great value to me.

The Good Life was packed—to bite line from De La Soul—The Good Life was darkly packed. American traditional values used to make it formally and explicitly illegal for Africans to come together in public. So the image at left from Freestyle—The Art of Rhyme has great value to me.

As a young poet of the 1990s in Los Angeles, I was effectively a street performer. A political boundary was drawn in my mind marked by Wilshire Boulevard. Public gatherings north of Wilshire Boulevard meant ‘fake shit’ (people who are not from California are free to pour on their stereotypes about people living in California in general and Los Angeles—especially Hollywood—in particular)—gatherings south of Wilshire meant a generous helping of darkly packed authenticity. But, of course, the people of the darker tone are free to sing lighter notes and stray from the bass as Icarus flies into the Sun.

As a writer, I was an outsider to the freestyle movement. But my respect for it lasts to this day. Poetry for me is an evolutionary or progressive process. Eventually the poet should journey through imitation and recitation and become an incarnation to speak poetically from the heart—without a script in the manner of a not-quite-holy prophet. The ‘authentic’ audiences south of Wilshire were interactive. There was the African call and response. When a Bryan Wilhite poem came from me to the audience, they had no reason whatsoever to conceal from me their opinion of it. I took this social support for granted and expected to spend the rest of my life in a progressive conversation with the community. I was wholly incorrect about this assumption.

It should go without saying that The Good Life is closed now. It was a family-owned business founded by a female and male in marriage. I see no replacement of this institution south of Wilshire. 5th Street Dick’s Coffee Company does come to mind but…

1580 KDAY Days of the Big Beat

Crenshaw Boulevard, south of Adams and North of, say, Manchester is symbolic of one of the last relatively functional African communities in the world, after the birth of Christopher Columbus—and I say this with the streets of Harlem and Atlanta in mind. It feels like it is shrinking every day. You would think that all of the chocolate-colored basketball players that passed through the Los Angeles Lakers would systematically organize some kind of multi-decade financial impact on the home-team turf but only one Laker, Magic Johnson sets this tone to a tune that I can almost hear. But that is now and this is then: 1580 KDAY radio station used to sit right in the Black heart of Crenshaw Boulevard. I recall it as one of the first radio stations to play hip hop music so I enjoy seeing the KDAY sign again in Freestyle—The Art of Rhyme. There were other Black radio stations up off Crenshaw but as Chuck D says on wax, “Radio stations: I question their Blackness. They call themselves Black but we’ll see if they’ll play this.” 1580 KDAY brought the noise.

Crenshaw Boulevard, south of Adams and North of, say, Manchester is symbolic of one of the last relatively functional African communities in the world, after the birth of Christopher Columbus—and I say this with the streets of Harlem and Atlanta in mind. It feels like it is shrinking every day. You would think that all of the chocolate-colored basketball players that passed through the Los Angeles Lakers would systematically organize some kind of multi-decade financial impact on the home-team turf but only one Laker, Magic Johnson sets this tone to a tune that I can almost hear. But that is now and this is then: 1580 KDAY radio station used to sit right in the Black heart of Crenshaw Boulevard. I recall it as one of the first radio stations to play hip hop music so I enjoy seeing the KDAY sign again in Freestyle—The Art of Rhyme. There were other Black radio stations up off Crenshaw but as Chuck D says on wax, “Radio stations: I question their Blackness. They call themselves Black but we’ll see if they’ll play this.” 1580 KDAY brought the noise.

Brian Coleman writes for Gentle Jones:

Aside from just breaking new music, KDAY was innovative in keeping their name and their faces out in the communities of Los Angeles, the kids who were the station’s core. But these weren’t friendly meet-and-greets at malls and industry gatherings. These were concerts and events in the deepest gang ‘hoods in LA, at the height of the city’s blood/crip warfare. The station’s head of public relations, Rory Kaufman, oversaw and attended these events, no matter where they were.

Back in the KDAY days of the Big Beat, Bryan Wilhite (a.k.a. rasx()) and R/Kain Blaze were two of “the kids.” Kain and I performed this rap song called “The Boom of the Bomb” at 190-something rec’ center in Compton. I am not going to tell you what I was wearing but these were the words I was saying:

Let the super powers summit. ’Cause we ain’t wit’ it. ’Cause it’ll only take a minute. I want a future time to get over—don’t want to learn just to be burned by an inter-governmental super nova. Peace get on it! Foreign policy for government! The red-white-and-blue-crew got a stealth bomber B2, thinking they can win it! But again—again I say: We ain’t wit’ it! I protest! I gotta rap it: The Boom of the Bomb!

Understand that these were the original words of a 17-year-old rapper, me. Do you think a big record company would want to celebrate this kind of inner-city mind? Do you think that this tone of Black thought in rap should become commonplace and expected in rap music? Would you hear these words on Clear Channel? Not all rappers coming out of the West Coast were like NWA. Tupac! Tupac! Why was yo’ big head so hard?

But understand that when I did perform this rap at the rec’ center, my use of the word “’cause”—a contraction of the word because was misheard by a few wanna-be gangsters in the audience. They thought I was making a reference to the Crips gang. The “Cuzz” were opposed to the Bloods. —So understand that there is an untold story about bright, intelligent, young people in hip hop music who did not envy the oppressor to incarnate oppressor violence and exploitation. Tupac, KRS1, Chuck D, Sistah Souljah and many, many others have said quite profound words that are not repeated because it does not fit in with the political ideology of the listener—and of course the media publisher. This is why I am never surprised that my work is rarely respected or confronted and often ignored. These words are here to dismantle you because you are trapped in this language. These words are here to break these words. There is a positive side to broken English—and many are afraid that they will never speak again without this language. Those that are keeping it real ain’t tryin’ to hear me.

You can hear a studio demo of the Boom of the Bomb (with R/Kain Blaze on a mono guitar) at rasx.megafunk.com under “College Experiments” (you might not find the song—I will improve the interface later). R/Kain Blaze is lately in collaboration at GarageBand.com. And to get back to the wardrobe issue: let me say that I am exceedingly pleased that no photographs of me were taken during my KDAY days—especially when I shared the same stage (separately) with Ice-T during a concert called “Back to Pacoima.” What was I thinking? Why was my big head so hard! To put this wardrobe issue into perspective, kids, extrapolate over to a brother I sat across the table from once in the KDAY offices, his Jheri Curl juice steady drippin’. Back then, his name was Shakespeare in a group called the World Class Wreckin’ Cru. Today, you know his monkey ass as Dr. Dre. When you look carefully, you can see how this 1980s ‘wardrobe issue’ came back to haunt Dr. Dre in Peter Spirer’s Beef or Beef II—I can’t remember which one.

Medusa… Smokin’!

This screenshot of Medusa, of Los Angeles, may seem unflattering. On the 1970s elementary school yard, we would use the words “snaggle toof” but I’m only saying this because my heart is broke by her. You see I cold stepped to her back over 15 years ago and I got her pager number. And I straight blew up her pager, homes. But she never called me back. Dzzam! Cuzz!

This screenshot of Medusa, of Los Angeles, may seem unflattering. On the 1970s elementary school yard, we would use the words “snaggle toof” but I’m only saying this because my heart is broke by her. You see I cold stepped to her back over 15 years ago and I got her pager number. And I straight blew up her pager, homes. But she never called me back. Dzzam! Cuzz!

I just could not resist recording the memory of this woman from Freestyle—The Art of Rhyme. She is emblematic of what captivated African women would call “the strong Black woman.” I ran my James Brown test on her and this is what I came up wit’:

- She is boss and she does draw a crowd.

- She does walk like she got the only lovin’ left.

- She does use what she got to get just what she want.

You may wonder in feminist hostility why I am not talking about the words of Medusa, her lyrics—her message. To be honest, I have not heard one of her songs and I left a message and she cold didn’t get back to me. Of course you are free to draw your sexist conclusions in the same manner a racist draws their fucked-up, pediatric, rusty tricycle kickstand conclusions. When you provoke me, you will find that my women voices over and above Medusa are Nina Simone and Millie Jackson. “What about a female rapper?” you ask. I can only recall the talents and grace of that one bad sistah from Digable Planets—too many female rappers passing by me seemed too formed and deformed by patriarchal male influence. Such is the “mis”-education of Lauryn Hill as maintained by Sony Music.

Bad rumors inform me that Medusa is not interested in getting my attention or anybody like me—especially as I do not smoke weed. Feel free to ask her yourself, she still may be performing at FAIS DO-DO here in Los Angeles. I can’t be sure but try to sort out http://www.onebadsista.com/. By now, I am sure she replaced her old pager with a mobile and eventually my number did change.

That screenshot of Medusa may seem unflattering but I likes that Afro and I hate the Black-plastic hair, blue jeans and pumps crippling our “strong” sisters today.

Boots of The Coup

Medusa is not the only one that can bring effects of the blowout comb! Boots of The Coup at left is representing the unbreakable, masculine comb effects—no cheap imitations in Freestyle—The Art of Rhyme. The sideburns are real. This last screenshot finds me trying to end this thang on positive polarity—the positive tip. Let me let Boots represent for Mos Def and the other rappers/freestylers in this documentary film that posses my respect. Boots is the kind of brother that puts that actor that from A Huey P. Newton Story in his rap videos, so he’s more than ready to represent. Here is Boots free-styling about gangsta rap as a political movement:

Medusa is not the only one that can bring effects of the blowout comb! Boots of The Coup at left is representing the unbreakable, masculine comb effects—no cheap imitations in Freestyle—The Art of Rhyme. The sideburns are real. This last screenshot finds me trying to end this thang on positive polarity—the positive tip. Let me let Boots represent for Mos Def and the other rappers/freestylers in this documentary film that posses my respect. Boots is the kind of brother that puts that actor that from A Huey P. Newton Story in his rap videos, so he’s more than ready to represent. Here is Boots free-styling about gangsta rap as a political movement:

Political Raps aren’t popular today because rap groups have a short life span… Rappers have to be in touch with their communities no matter what type of raps you do otherwise people won’t relate…Political Rap groups…..offered solutions only through listening….They weren’t part of a movement… So they died out when people saw that their life’s were not changing…

On the other hand, gangsta groups and rappers who talk about selling drugs are a part of a movement. The drug game has been around for years and has directly impacted lives and for some many it’s been positive in the sense that it earned people some money. Hence, gangsta rap has a home…

What is more is that gangsta rap is a compelling argument for exploitative capitalism (is that redundant?). The final, social realization of Gangstarap is an African dictatorship—a cleptocracy. And this Alexandrian/Orewellian/Ike-Turner-ian future is what awaits all my people who are keeping Rex real. My people perish for lack of knowledge.

When I question my own egocentrism and develop to minimize its validity, I am free to collectivize and see what Boots, Mos Def and others (Chuck D of course) are bringing as a voice on the mic’ for the masses—see that they are representing for me what I would do had I “blew up” back in the day… Actually, they are doing more than what ‘I’ could have imagined back in the day. Much respect to y’all. J’ah Jireh…

This article was originally serialized over several days in the rasx() context, the kintespace.com Blog.